Article © Julian Dignall, uploaded May 03, 2021.

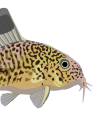

Much of the Rio Xingu that is either a day or two's boat ride up or down stream of Altamira is pretty fast flowing clearwater. Often it is shallow enough to wade in, in places it is tens of meters deep if not more. Here many of the fishes we've talked about so far live in submerged cracks or fissures in the huge lumps of dark granite found almost everywhere. However, there are many other biotopes to be found. Where the clear water slows to near standing in any area it can quickly bloom with algae. While it can be found in faster flowing water, L047, the Mango or Magnum Pleco (Baryancistrus chrysolomus) appears to favour such slower waters and it is certainly coloured to fit right in the greenish soup of the near still waters where it can be found.

While a similar shape, size and general attitude of its more commonly encountered cousin the gold nugget pleco (B. xanthellus), the mango pleco differs in so far as it's a bit more of a herbivore than a detrivore. It is also lime green with banana yellow edges to the unpaired rayed fins. In the aquarium, the difference in diet doesn't make much of a difference beyond making newly imported individuals a shade easier to acclimatise with typical catfish sinking pellets and the like. They're also more tolerant of sub optimal water conditions. In short, an easier pleco to keep but that shouldn't stop you from offering frequently water changes (they eat a lot, and therefore produce a surprising amount of waste) and adding an airstone if you're not setting them up in a tank with power filtration. Current may not be mandatory, but low levels of dissolved oxygen can spell disaster for Baryancistrus that like to be kept warm at around 27-32°C.

This might lead you to the conclusion they'd be a good addition for a discus tank. However, they could suffer from bloat if they eat too much discus food. A better discus tank option would be the more carnivorous Scobinancistrus spp. that are found in the Xingu (S. aureatus or L048) or similar species for the warmer north flowing Amazon tributaries such as the Rios Tocantins and Tapajos.

Baryancistrus chrysolomus, collected from the green water in the background

Baryancistrus chrysolomus, collected from the green water in the background Aphanotorulus emarginatus underwater in the same area

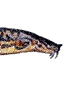

Aphanotorulus emarginatus underwater in the same area

Photographing or filming L047 underwater in green water was very challenging. I don't think anyone got a good shot due to the fact the water was 2-4 metres deep. However, the fishermen we were travelling with did manage to collect a few. Aphanotorulus emarginata (L011 is given to those found in the Xingu) is also present in the more sluggish waters where even foot long adults hang out in less than a metre of water column. These are out and out omnivores, hardy and as easy to keep as common plecos. They do grow quite large, but are elongate, colourful (sporting a red to orange flash in the lower caudal fin lobe) with an attractive black spotting pattern over a sandy beige base colouration. A really nice medium sized pleco than will work well with small or medium sized fish up to and including something like an Oscar (Astronatus occelatus). Meanwhile, back on the Xingu, someone spotted a large electric eel in the murky green water and I called it a day. While I'd love to see one of these large fish in the wild, I was certain I'd rather do it in water where I could see where I was standing even if it was still.

Volta Grande, Cachoeira do Jericoá

Volta Grande, Cachoeira do Jericoá The river roars down an 8m drop

The river roars down an 8m drop

At the other end of the scale, are the crashing waterfalls of the Volta Grande. This is where the river drops many meters over less than a mile and the result is roaring torrents and highly oxygenated warm water. Snorkelling here was awesome, but challenging in so far as you had to hold on to avoid being gently (at first) pulled downstream in the direction of the nearest waterfall. I lost my grip a couple of times and the acceleration of the pull of the water I experienced made me much more careful. It is such an intense assault on the senses, the roar of the water, the amazing plethora of aquatic life, the clear warm water and the hot tropical sun multiplied by the excitement of a fishy find or the capture of some photograph or memory. And so it was when I first found a Rio Xingu Panaque. I was just hauling myself out the most pleasant 30 minutes or so of sitting in a pool of medium current watching gold nugget plecos, several species of tetra, a family of pike cichlids and the old huge Retroculus swim by. As an aside, the rapids dwelling cichlids (in this case, Retroculus xinguensis) are a great watch underwater. Adults were not too frightened by my presence when I stayed static in the water and watching how effortlessly they navigated strong current was fascinating. After a while, they got used to me and started looking for food or defending territory - even for the catfish hardcore, it was a magical experience. So, I was thinking about cichlids when I saw something move on a rock near the water surface. I drifted over. It took me a long time, maybe tens of seconds, to realise I was looking at a 3" juvenile Panaque. It was perfectly camouflaged, the black lines and sage green base colour made it hard to make out even from a meter away. I saw it eating the roots of submerged river weed and a rather large penny dropped.

- Drone footage of the Xingu's Volta Grande, Cachoeira do Jericoá, ca. 55 km east-southeast of Altamira

Log in to view data on a map.Google satellite map of the same area

Compared to other places you find Panaque, there is very little wood in the Xingu rapids. Sure, there is the odd bit here and there but most of it has long been blasted downstream. I've been to the type locality of the Royal Pleco, Panaque nigrolineatus in Venezuela - there is so much wood in the water you can hardly move and indeed collecting those plecos is not much harder than scraping a net along a piece of barely submerged wood. But in the wood deprived Rio Xingu, many, myself included, have pondered what these fishes eat and this was always a bit of a mystery. Prior to the description of Panaque armbrusteri from the Rio Tapajos, Brazilian Panaque (Royal Plecos, not the smaller Panaqolus) were known as L027 often with an a,b,c or d suffix e.g. L027b. Attempts to split them up into groups only made sense once we understood where they came from and the differences between young and adult forms. There are, probably, close relatives of P. armbrusteri in the Rios Araguaia, Tocantins and Xingu. They appear with fantastic and confusing tradenames like Teles Pires Royal Pleco, Platinum or, my favourite, Royal Thunder Pleco. I think most if not all with end up as new species and certainly the one I was swimming with in the Xingu is the most different of all large striped Panaque from the Venezuelan type species. It is flatter especially when young, it doesn't have classic spoon shaped teeth when older and it was a revelation to me to figure out this is because it eats, at least some of the time and as a juvenile at least, river weeds and not wood.

Juvenile Panaque habitat

Juvenile Panaque habitat

As we returned to the boat I was still pondering this discovery. I further realised that in wet season when the river rises above the rocks we had been walking on, that all that river weed would be gradually submerged, slowly exposing a Panaque feast to the awaiting hordes. It was sobering to also think that, because of the Belo monte dam, that was the highest water this part of the Rio Xingu was every going to see again. It would likely reduce further while also not being subject to the annual changes in water throughput. My mind was still miles away pondering the fate of the Xingu Royal pleco when it very abruptly came back to worry rather more directly to my own fate. We were pushing back upstream in rapids and the outboard motor had cut. It was not for re-starting. We were drifting backwards and picking up speed. Nate, one of our local fisherman, instinctively dived (without regard to hidden rocks) into the water and swam like a man possessed to the nearest large rock. The boats pilot expertly threw him some line and, with a few heart stopping slips and pulls, managed to secure our boat to the rocks. He pulled the boat to and we got out. It was a nice spot, which was just as well as, with no motor, it looked like we may be visiting for a while.

While I could explain how we got out of that pleasant pickle, I should explain a little about keeping the Xingu Royal Pleco in captivity. It will still "have a go" at wood, but this is a fish that as a juvenile will dine out on sweet potato or similar vegetable with gusto. Otherwise, it's classic Panaque. Juveniles have rusty red pectoral fins and reddish eyes with a translucent crescent shape in the caudal fin; foot long plus adults are incredibly impressive fishes that will hold a large territory which they will defend robustly. As adults, they appear to have a pale olive green stripes on a black background (as opposed to the other way around in Panaque nigrolineatus) with fin rays picked out in the lighter colour on otherwise solid black fins. Water quality is important, but these fishes are hardy if well fed. Upon buying them, a quarantine tank is a good idea where you can feed a lot and water change a lot especially if, as many are, the fishes have not eaten well for a few weeks.

Others and I have written on this before, but it's worth re-iterating here that many plecos eat pretty much all the time. Reproducing this in the aquarium is not simple and think about the type of foods we provide (for example, gel based foods, or natural foods like decaying wood or algae covered stones) are important to consider in addition to tradition options such as catfish tablets, pellets and to a lesser degree live or frozen foods. But rather than prescribe a diet, what I would like to do her is show you how a gold nugget pleco (Baryancistrus xanthellus) feeds in the wild. These pictures are intended to give the reader something to think about. The challenge then, for the fishkeeper, is to find a way they can simulate this in a filtered glass box of warm water.

A 'nugget's' view of its world, every surface is a dinner plate, covered with protein poor biofilm to be ingested through constant grazing

A 'nugget's' view of its world, every surface is a dinner plate, covered with protein poor biofilm to be ingested through constant grazing Youngsters typically feed closer to shelter or at night.

Youngsters typically feed closer to shelter or at night.

Consider how much adult plecos need every day, and how long they must feed for to obtain this. Even individuals this size feed in shallow clear water and can readily be seen. Again, this one is from the Volta Grande.

Consider how much adult plecos need every day, and how long they must feed for to obtain this. Even individuals this size feed in shallow clear water and can readily be seen. Again, this one is from the Volta Grande. The dark area in the photo is "clean" rock which I timed an adult pleco on for just over two minutes before I scared it off. This is about 40cm at its longest width.

The dark area in the photo is "clean" rock which I timed an adult pleco on for just over two minutes before I scared it off. This is about 40cm at its longest width.

There are some underrated and not commonly exported plecos from the region too. For example, Peckoltia feldbergae, described by Renildo de Oliveira, Lucia Rapp Py-Daniel, Jansen Zuanon and Marcelo Rocha in 2012. Only three years later,it was moved by Jon Armbruster, David Werneke and Milton Tan transferred this species to another genus, Ancistomus. Such shifts are common in the world of plecos because there is a remarkable amount of fishes (and thus data) which is only now being processed and addressed. Before being described we knew this species as L012 and L013 (L013 was a young L012). Both are very similar to L163 from the Rio Tocantins. Ancistomus are more elongate than Peckoltia and this is a pretty example with darker spots on pale cream to sandy coloured body with an attractive orange seam to the edges of their major fins. Hardy and easy to keep, it is only because there are many more sought after species in the Rio Xingu that we do not see these fishes more often.

A Rio Xingu pleco I've never seen for sale in the trade is the green species of Baryancistrus endemic to the area around the Belo Monte Dam. It is the same shape as a gold nugget pleco (B. xanthellus) and appears to do pretty much the same things. I call it green, but it's greenish with a bit of brown - rather like common cushion moss we find in the UK. I encountered this fish snorkelling in strong clearwater current. Adults were at home in about 1m of water and less skittish than they spotted cousins. Perhaps the green colouration helps with camouflage. In this locality we also saw a river otter eating something that looked suspiciously like a large pleco - if so, surely these larger plecos do not have many other natural predators and certainly none that occur in great numbers given the local caimen have been hunted out of existence. The green Baryancistrus has no l-number, as it will likely be wiped out by the Belo Monte Dam, it may pass into history with very few people even knowing it was ever there. It is nice to note it here.

Baryancistrus sp. `Belo Monte`, habitat

Baryancistrus sp. `Belo Monte`, habitat Baryancistrus sp. `Belo Monte`

Baryancistrus sp. `Belo Monte`

- Underwater with the Belo Monte Baryancistrus

Log in to view data on a map.Google satellite map of the same area

There are areas of the Rio Xingu where one can find submerged wood. Many of the larger islands have trees and they can be found fallen in the water. Where the current is sheltered, perhaps by a natural harbour, the trees remain. Pretty much anywhere in tropical South America, sunken wood means you will find a representative of the genus Panaqolus. They eat wood, they live on it and they breed in and around it. Further downriver from the town of Vitoria do Xingu we edged into such a spot. There was little current and several fallen tree trunks ran from the island edge into the water. On entering the water, I could see this was a much more dangerous place to snorkel than the rocky places we had been before. There were many logs and branches underwater, just a little carelessness could get you snagged or trapped. Furthermore, there is a common species of palm tree in the Amazon that has 2-3" spines all up it's trunk. While wandering around the rainforest, they are relatively easy to spot and avoid. While swimming among them, they are especially tricky.

- Underwater with Panaqolus tankei

Log in to view data on a map.Google satellite map of the same area

We travelled overland from Altamira to Porto Vitoria do Xingu and hired out speedboats to explore downriver. Here the river is slower and there is a lot of large marginal vegetation. We're told this is the only area to find populations of Discus (Symphysodon) on the Xingu. While that may have been of interest to some, I was interested in less flashy things and was keen to get in and amongst the abundance of submerged wood in this locale. I had only been in the water ten minutes or so when I saw a few tell-tale darting shapes on the submerged logs. Soon enough I was watching L398, the Rio Xingu Panaqolus up close. After my trip this species was named for Andreas Tanke (Andi), a friend of PlanetCatfish, and someone who has shown the greatest interest in all the brown, striped and really quite similar members of the genus Panaqolus. As these fishes will rarely leave the log they are on, it is a simple matter of swimming around the log to gain a good vantage point with which to observe them. I found one close enough to the surface that I could watch it while I was breathing air through my snorkel. After a few minutes it forgot about me and went about it business gnawing away at its home industriously. I've written before about the fun and considerations of keeping Panaqolus in the aquarium. In short, all the wood waste they produce is hard work for filters but they are otherwise easy to keep in a tank with plenty of wood. Try collecting your own lichen enriched branches from local woodland - they love it!

A poignant reminder of the strength of the river, the tracks from this heavy machinery are all that remains of this human mishap.

A poignant reminder of the strength of the river, the tracks from this heavy machinery are all that remains of this human mishap. The sheer scale of a tiny part of the river is shown here by the two-foot wide drone (bottom, left) flying above rapids running at low-water levels.

The sheer scale of a tiny part of the river is shown here by the two-foot wide drone (bottom, left) flying above rapids running at low-water levels.

During high water, sand polishes rocks to the point that, above water and bone dry, they look oily - these are rocks as big as a human and being amongst them is otherworldy.

During high water, sand polishes rocks to the point that, above water and bone dry, they look oily - these are rocks as big as a human and being amongst them is otherworldy.

The blockbuster movie Avatar was written and director by James Cameron (Titantic, Alien, Terminator etc.) and starred Sigourney Weaver. Big Hollywood names but ones also that have spent time in the Xingu trying to bring the spotlight of fame normally shone on them into focus on the plight of the area and particularly the indigenous people who have been forceably moved off their land as part of the dam project. The plot of Avatar is a direct representation of this situation in Brazil - written by Cameron who knows the issues well - but even such high profile attention only slowed the dam's completion.

My time in the Xingu came to an end. Watching my last sunset my sadness at leaving was multiplied by the perilous future all these fishes faced. The political power and perceived benefit to the nation of a dam that would be as inefficient as it would be destructive to the surrounding land did not make me feel great about being human. However, other humans are making great progress in captive breeding efforts of many of the species I encountered and at least some of them seem fit to escape extinction as their part of their river runs ever drier.

Sunset on the Rio Xingu

Sunset on the Rio Xingu

Back to Shane's World index.